King Tut's Tomb Undergoes Digital Preservation and Reproduction

Egyptian specialists are recreating Tut's tomb to spare it from stress caused by tourism.

February 10, 2010

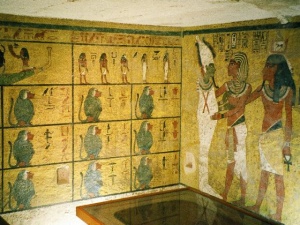

Imagine a dark, dank, cavernous yet cramped space. The air inside hangs heavy; the heat lingers. Each busy day can usher in as many as 1000 people, although the average height of the chamber measures only about 12 ft., the average width just over 13 ft. Welcome to KV62, known more colloquially as King Tut’s tomb. Tutankhamun’s burial chamber, discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, had been spared the brunt of devastating ravages by tomb raiders who left other tombs devoid of precious metals and fine goods. As the entrance had been essentially buried, the contents were nearly intact. When Carter descended the staircase, untouched for thousands of years, Tut ascended into the limelight.

Nowadays, the question is how to protect and preserve a national treasure from a different kind of harm, as the tourist industry can be tough on delicate environments. A solution comes in the form of a replica, an exact facsimile that would equal the original in detail, presented in the same shades of vivid pigment. Several collaborators undertook the ambitious project: The Supreme Council of Antiquities, Factum Arte, University of Basel, The Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt, and the Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation. The initiative encompasses three tombs (and is sure to inspire more, issues of funding notwithstanding), those of Tutankhamun, Nefertari, and Seti I. The facsimiles will reside at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings in a site chosen by Dr. Zahi Hawass.

In brief, the components of the project are thus: 3D digital recording of the three tombs, color recording of all decorated surfaces, facsimile creation, permanent accompanying exhibitions, concomitant digital archives of all data for the purpose of future conservation, and a permanent laser scanning unit within the Supreme Council of Antiquities (for whom the Seti laser scanner was designed). Factum Arte’s report tosses around phrases the likes of, “highest resolution large-scale facsimile project ever undertaken” and “will set new standards for the use of facsimiles in conservation”; the work gives new meaning to the phrase detailed documentation. The entrance fees to the architectural-doppelgangers will provide welcome revenue with an estimated 500,000 visitors per year, and, in the case of Seti’s tomb, might hint to the USA and Europe that Egypt wants her fragments back (These fragments, residing elsewhere, will be re-integrated into the facsimile).

The Tut phase of work began in March and ended in May of 2009. The crew worked alongside visitors, many of whom questioned the physical impact of their presence on the tomb. With funding from the Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation, a new laser was built with hi-res digital cameras and a feature allowing the capture of dark colors and light areas simultaneously. The 3D data, recorded with the Seti scanner, is comprised of 100,000,000 measured points per square meter. Staff utilizing a Canon EOS5DII produced 8,000 photographs with a resolution of 600-800 dots per inch at a scale of 1:1 (as a point of reference, the human eye can only distinguish up to about 250 dpi). Conservator Naoko Fukumaru used sticks of color samples to match and document over 500 discreet colors. Such intricacy will enable future specialists to measure the slightest degree of change in cracked paint or growing microorganisms. Construction on the facsimiles began in Fall 2009, and similar replicas have already been install at the tombs of Beni Hassan in Minya, Giza and Saqqara.

With this project, the Egyptians are setting a fantastic precedent for other heritage authorities to protect their sites by creating accurate replicas. The same could be done for sites in war-torn or otherwise dangerous locations; Babylon springs to mind. What might be the larger implications of closing original sites and opening facsimiles? In theory, such facsimiles could be installed anywhere. Is this good or bad; what scenarios might transpire?

___________________

About the Author

Angelica Nava is a San Francisco based writer with a degree in Classics from Stanford University.

Nowadays, the question is how to protect and preserve a national treasure from a different kind of harm, as the tourist industry can be tough on delicate environments. A solution comes in the form of a replica, an exact facsimile that would equal the original in detail, presented in the same shades of vivid pigment. Several collaborators undertook the ambitious project: The Supreme Council of Antiquities, Factum Arte, University of Basel, The Friends of the Royal Tombs of Egypt, and the Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation. The initiative encompasses three tombs (and is sure to inspire more, issues of funding notwithstanding), those of Tutankhamun, Nefertari, and Seti I. The facsimiles will reside at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings in a site chosen by Dr. Zahi Hawass.

In brief, the components of the project are thus: 3D digital recording of the three tombs, color recording of all decorated surfaces, facsimile creation, permanent accompanying exhibitions, concomitant digital archives of all data for the purpose of future conservation, and a permanent laser scanning unit within the Supreme Council of Antiquities (for whom the Seti laser scanner was designed). Factum Arte’s report tosses around phrases the likes of, “highest resolution large-scale facsimile project ever undertaken” and “will set new standards for the use of facsimiles in conservation”; the work gives new meaning to the phrase detailed documentation. The entrance fees to the architectural-doppelgangers will provide welcome revenue with an estimated 500,000 visitors per year, and, in the case of Seti’s tomb, might hint to the USA and Europe that Egypt wants her fragments back (These fragments, residing elsewhere, will be re-integrated into the facsimile).

The Tut phase of work began in March and ended in May of 2009. The crew worked alongside visitors, many of whom questioned the physical impact of their presence on the tomb. With funding from the Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation, a new laser was built with hi-res digital cameras and a feature allowing the capture of dark colors and light areas simultaneously. The 3D data, recorded with the Seti scanner, is comprised of 100,000,000 measured points per square meter. Staff utilizing a Canon EOS5DII produced 8,000 photographs with a resolution of 600-800 dots per inch at a scale of 1:1 (as a point of reference, the human eye can only distinguish up to about 250 dpi). Conservator Naoko Fukumaru used sticks of color samples to match and document over 500 discreet colors. Such intricacy will enable future specialists to measure the slightest degree of change in cracked paint or growing microorganisms. Construction on the facsimiles began in Fall 2009, and similar replicas have already been install at the tombs of Beni Hassan in Minya, Giza and Saqqara.

With this project, the Egyptians are setting a fantastic precedent for other heritage authorities to protect their sites by creating accurate replicas. The same could be done for sites in war-torn or otherwise dangerous locations; Babylon springs to mind. What might be the larger implications of closing original sites and opening facsimiles? In theory, such facsimiles could be installed anywhere. Is this good or bad; what scenarios might transpire?

___________________

About the Author

Angelica Nava is a San Francisco based writer with a degree in Classics from Stanford University.

Original Tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings. Photo taken by Hajor, Dec.2002. Released under cc.by.sa and/or GFDL.

Tuthankamen's famous burial mask, on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Image courtesy of Bjørn Christian Tørrissen.