Moen jo Daro - New Threats to Indus Valley Civilization

Rising water tables and violent vandalism endanger site's future

January 4, 2010

About the Author

Parveen Talpur is a New York based writer and historian. Her research at Cornell University (1990-97) focused on the decipherment of Moen jo Daro seal symbols. The results of her research are published in the Wisconsin Archaeological Reports, Vol 3, 1994, Department of Anthropology University of Wisconsin, Madison. The second phase of her research is published as a book The Evidence of Geometry in Indus Valley Civilization 2500-1500 B.C. Parveen Talpur's latest book, Moen jo Daro: The Metropolis of Indus Valley Civilization 2600-1900 B.C, is currently under publication.

___________________

The traveling exhibition ‘Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul’ that ended in September 2009 at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art proved that archaeological sites and artifacts can be salvaged from neglect, environmental hazards, and vandalism during even the most adverse circumstances.

Over 200 pieces exhibited the culture and cross-cultural influences of the Hellenistic, Oriental, Roman, and Indian worlds with Bronze Age Afghanistan. Each piece is a representation of the valiant tale of their redemption from three decades of turmoil in Afghanistan. The country is also working to retrieve its ‘lost’ heritage through the restoration of the Buddha sculptures and relief in Bamiyan, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The two colossal Buddha statues, largest in the Buddhist World, had survived in the Bamiyan mountain walls for two thousand years, standing robed and exalted in niches carved and customized according to their stature. After being blown to pieces, a massive restoration project began; it will cost an approximate sum of $50 million. In the face of an ongoing insurgency, Afghanistan continues to move ahead with its resolve and looks forward to help from UNESCO and Japan, who are already supporting the restoration of the Bamiyan heritage.

Afghanistan’s cultural destruction should, however, be a revelation for countries that face similar risks. Pakistan, being within easy reach, can become the next target for cultural heritage destruction as the Taliban and Islamic militant groups multiply within the country. Attempts to vandalize Pakistan’s Buddhist heritage in the Swat Valley have been reported since 2007 by Vishakha Desai, the Director of Asia Society, New York. Pakistan’s antiquity is already vulnerable. In fact, the discovery of one of Pakistan’s most important heritage sites belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization begins with the dismantling of ruins as the site was being used as a quarry for bricks. Harappa’s kiln-baked bricks were recycled to lay the foundation of a modern railroad; but this story is stale as greater dangers loom over almost all Pakistani sites. To relieve some strains, Islamabad has handed over 130 heritage sites to the provincial government of Sindh. Many of these sites are badly preserved. Moen jo Daro, the largest and most elaborate city of the Indus Valley Civilization, is also located in Sindh, 400 miles from its counterpart, Harappa, in the province of Punjab. However, Moen jo Daro remains under the protection of the federal government.

The Indus Valley Civilization has more than 1500 known archaeological sites and stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas in the North, to the Arabian Sea coast in the South, and from the Iran-Pakistan borderlands in the West to Gujrat in India in the East. Moen jo Daro is the queen of these sites and has distinct and unique features, providing it enlistment as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Town planning is one of the most obvious of these unique features. Constructed over a grid plan, Moen jo Daro’s layout is as geometrical as any modern city. Its major streets run North-South and are intersected by smaller lanes at right angles. The main street is wide enough for the passage of three bullock-carts at a time. Moen jo Daro is also known for its civic and hygienic construction through the use of an efficient network of drains to carry used water outside the city. The drains were covered and ran parallel to the streets, having no sharp turns to ease the flow of the water and prevent blockages at sharp turns.

The city is divided into two main areas: residential and the ‘citadel mound’ (which is how early archaeologists referred to the communal area). The mound area had fortified walls and gates. The most impressive and geometrically perfect structure is the Great Bath. The Bath is an eight feet deep bathing pond with flights of brick steps on two opposite sides providing access to the floor where, most likely, a water cult was performed. Near the Bath is a Pillared Hall, marked with the remains of twenty pillars arranged in four rows. Some experts suggest that the Hall might have been the residence of a ‘high priest’ or a group of priests. Approximately three hundred houses of the lower city (the residential area) have been excavated. Some houses had two floors and were elaborately built with courtyards and bathrooms that had sloping floors so water would flow through chutes to the street drains. According to an early estimate Moen jo Daro was spread over an area of 76.6 hectares with a population of 41,250 (1); but this has changed: “the inhabited area of Mohenjo-daro is actually greater than 250 hectares and therefore maybe held considerably more people than calculated by Fairservis” (2).

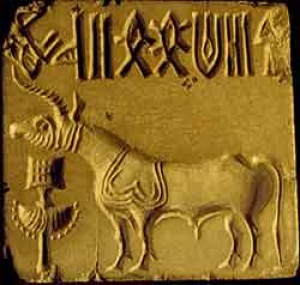

Although the ruins of Moen jo Daro have revealed a large number of artifacts, the lack of written material means not much is known about the social organization, culture, and ideology of its inhabitants. But the discovery of a large number of seals (over 1200 to date) might hold some clue to the missing information. The seals are inscribed with pictographs that many archaeologists believe to be a system of writing representing an unknown ancient language. The majority of the seals are one-inch-square-shaped and engraved with a row of pictographs on the top and the image of an animal on the lower section. The animal is depicted facing an upside down lamp-like object, considered to be a feeding bowl or an offering stand. The most common animal images are of humped bulls, elephants, and unicorns. This one-horned animal, was mentioned in the ancient Greek record first by Ctesias in his Indica. He did not consider it a mythological character but as real. Being a doctor and a historian, Ctesias’ account was considered authentic and even Aristotle attributed the unicorn to India (3). More than a hundred attempts have been made at deciphering the seals’ pictographs, but the brevity of the inscriptions and lack of a bilingual dictionary (the Rosetta Stone, for example, had a trilingual inscription) has allowed the mystery to continue challenging the experts. The seals did help, however, with establishing the chronology of the Indus Valley Civilization. Based on the discovery of few Indus seals at Ur, the seals were cross-dated with Mesopotamian artifacts and it was suggested that the Indus culture lasted between 2300-1700 B.C.E. (recent dating has varied these to 2600-1900 B.C.E.)

The Indus seals at Ur showed the Indus Valley Civilization to be contemporaneous with the Mesopotamian and Egyptian Civilizations, subjecting Moen jo Daro to an unworthy comparison of its utilitarian architectural remains with the monumental structures of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Moen jo Daro had failed in giving birth to an extravaganza of architecture, such as pyramids, palaces, temples and tombs, because the civilization did not mature to a state-organized society; it was arrested in an urban phase. The vast remains of the city of Moen jo Daro instead revealed the most remarkable feature of the civilization: its urban boom. Evidence suggests that the Indus society was not rigidly class divided and had no standing army, yet it had professional specialists such as dyers, weavers, farmers, potters, boat makers, carpenters, and scribes, to mention a few. This composition fully show-cased in Moen jo Daro makes it all the more important as it is a snapshot of a society prior to the development of a state-organized society. The remains of Moen jo Daro need to be preserved as it is an important record of the urban phase of the socio-cultural evolution of human society.

In 1964 a ban on excavation was issued by the government to protect Moen jo Daro from excessive erosion caused by a high water table. And in 1973, experts from the member countries of UNESCO and officials of the government of Pakistan prepared and approved a master plan suggesting methods to combat waterlogging and salinity to save the site. The master plan was updated in 2006, but the ban on excavation continues and much of the archaeology remains submerged in underground water table. It is true that the site has outlived the forecast made by H.J. Plenderleith in 1964, “If nothing is done to preserve them, all the existing excavations will crumble within the next 20 to 30 years and one of the most striking monuments of the dawn of civilization will be lost for ever”, but it may not be able to survive violent methods of vandalism threatening regions of Pakistan.

Fortunately new technology and “digital preservation” have come to the rescue of many sites the world over; now Moen jo Daro needs to get ready for its virtual survival, at the very least. Digitization is no longer limited to textual and photographic material and the whole site can be preserved, stored, and retrieved digitally. In the face of the current law and order situations in Pakistan, where tourists and experts may fear to visit the site, accessing its digital content can be a comfortable option for them, while ensuring complete records should hostile forces purposely destroy the ancient remains of the city.

REFERENCES

(1) Walter A. Fairservis, Jr., “The origin, Character and Decline of an Early Civilization,” in Ancient Cities of the Indus, ed. Gregory Possehl, Vikas, New Delhi, 1979.

(2) Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark, Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, Oxford University Press, Pakistan, 1998.

(3) International Standard Bible Encyclodedia:Vol 1, Wm.B. Eerdmans, 1979 ed.

Parveen Talpur is a New York based writer and historian. Her research at Cornell University (1990-97) focused on the decipherment of Moen jo Daro seal symbols. The results of her research are published in the Wisconsin Archaeological Reports, Vol 3, 1994, Department of Anthropology University of Wisconsin, Madison. The second phase of her research is published as a book The Evidence of Geometry in Indus Valley Civilization 2500-1500 B.C. Parveen Talpur's latest book, Moen jo Daro: The Metropolis of Indus Valley Civilization 2600-1900 B.C, is currently under publication.

___________________

Adverse Conditions for Archaeological Remains

The traveling exhibition ‘Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul’ that ended in September 2009 at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art proved that archaeological sites and artifacts can be salvaged from neglect, environmental hazards, and vandalism during even the most adverse circumstances.

Over 200 pieces exhibited the culture and cross-cultural influences of the Hellenistic, Oriental, Roman, and Indian worlds with Bronze Age Afghanistan. Each piece is a representation of the valiant tale of their redemption from three decades of turmoil in Afghanistan. The country is also working to retrieve its ‘lost’ heritage through the restoration of the Buddha sculptures and relief in Bamiyan, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The two colossal Buddha statues, largest in the Buddhist World, had survived in the Bamiyan mountain walls for two thousand years, standing robed and exalted in niches carved and customized according to their stature. After being blown to pieces, a massive restoration project began; it will cost an approximate sum of $50 million. In the face of an ongoing insurgency, Afghanistan continues to move ahead with its resolve and looks forward to help from UNESCO and Japan, who are already supporting the restoration of the Bamiyan heritage.

Afghanistan’s cultural destruction should, however, be a revelation for countries that face similar risks. Pakistan, being within easy reach, can become the next target for cultural heritage destruction as the Taliban and Islamic militant groups multiply within the country. Attempts to vandalize Pakistan’s Buddhist heritage in the Swat Valley have been reported since 2007 by Vishakha Desai, the Director of Asia Society, New York. Pakistan’s antiquity is already vulnerable. In fact, the discovery of one of Pakistan’s most important heritage sites belonging to the Indus Valley Civilization begins with the dismantling of ruins as the site was being used as a quarry for bricks. Harappa’s kiln-baked bricks were recycled to lay the foundation of a modern railroad; but this story is stale as greater dangers loom over almost all Pakistani sites. To relieve some strains, Islamabad has handed over 130 heritage sites to the provincial government of Sindh. Many of these sites are badly preserved. Moen jo Daro, the largest and most elaborate city of the Indus Valley Civilization, is also located in Sindh, 400 miles from its counterpart, Harappa, in the province of Punjab. However, Moen jo Daro remains under the protection of the federal government.

The Indus Valley Civilization and Moen jo Daro

The Indus Valley Civilization has more than 1500 known archaeological sites and stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas in the North, to the Arabian Sea coast in the South, and from the Iran-Pakistan borderlands in the West to Gujrat in India in the East. Moen jo Daro is the queen of these sites and has distinct and unique features, providing it enlistment as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Town planning is one of the most obvious of these unique features. Constructed over a grid plan, Moen jo Daro’s layout is as geometrical as any modern city. Its major streets run North-South and are intersected by smaller lanes at right angles. The main street is wide enough for the passage of three bullock-carts at a time. Moen jo Daro is also known for its civic and hygienic construction through the use of an efficient network of drains to carry used water outside the city. The drains were covered and ran parallel to the streets, having no sharp turns to ease the flow of the water and prevent blockages at sharp turns.

The city is divided into two main areas: residential and the ‘citadel mound’ (which is how early archaeologists referred to the communal area). The mound area had fortified walls and gates. The most impressive and geometrically perfect structure is the Great Bath. The Bath is an eight feet deep bathing pond with flights of brick steps on two opposite sides providing access to the floor where, most likely, a water cult was performed. Near the Bath is a Pillared Hall, marked with the remains of twenty pillars arranged in four rows. Some experts suggest that the Hall might have been the residence of a ‘high priest’ or a group of priests. Approximately three hundred houses of the lower city (the residential area) have been excavated. Some houses had two floors and were elaborately built with courtyards and bathrooms that had sloping floors so water would flow through chutes to the street drains. According to an early estimate Moen jo Daro was spread over an area of 76.6 hectares with a population of 41,250 (1); but this has changed: “the inhabited area of Mohenjo-daro is actually greater than 250 hectares and therefore maybe held considerably more people than calculated by Fairservis” (2).

Although the ruins of Moen jo Daro have revealed a large number of artifacts, the lack of written material means not much is known about the social organization, culture, and ideology of its inhabitants. But the discovery of a large number of seals (over 1200 to date) might hold some clue to the missing information. The seals are inscribed with pictographs that many archaeologists believe to be a system of writing representing an unknown ancient language. The majority of the seals are one-inch-square-shaped and engraved with a row of pictographs on the top and the image of an animal on the lower section. The animal is depicted facing an upside down lamp-like object, considered to be a feeding bowl or an offering stand. The most common animal images are of humped bulls, elephants, and unicorns. This one-horned animal, was mentioned in the ancient Greek record first by Ctesias in his Indica. He did not consider it a mythological character but as real. Being a doctor and a historian, Ctesias’ account was considered authentic and even Aristotle attributed the unicorn to India (3). More than a hundred attempts have been made at deciphering the seals’ pictographs, but the brevity of the inscriptions and lack of a bilingual dictionary (the Rosetta Stone, for example, had a trilingual inscription) has allowed the mystery to continue challenging the experts. The seals did help, however, with establishing the chronology of the Indus Valley Civilization. Based on the discovery of few Indus seals at Ur, the seals were cross-dated with Mesopotamian artifacts and it was suggested that the Indus culture lasted between 2300-1700 B.C.E. (recent dating has varied these to 2600-1900 B.C.E.)

The Indus seals at Ur showed the Indus Valley Civilization to be contemporaneous with the Mesopotamian and Egyptian Civilizations, subjecting Moen jo Daro to an unworthy comparison of its utilitarian architectural remains with the monumental structures of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Moen jo Daro had failed in giving birth to an extravaganza of architecture, such as pyramids, palaces, temples and tombs, because the civilization did not mature to a state-organized society; it was arrested in an urban phase. The vast remains of the city of Moen jo Daro instead revealed the most remarkable feature of the civilization: its urban boom. Evidence suggests that the Indus society was not rigidly class divided and had no standing army, yet it had professional specialists such as dyers, weavers, farmers, potters, boat makers, carpenters, and scribes, to mention a few. This composition fully show-cased in Moen jo Daro makes it all the more important as it is a snapshot of a society prior to the development of a state-organized society. The remains of Moen jo Daro need to be preserved as it is an important record of the urban phase of the socio-cultural evolution of human society.

Protection and Digital Preservation

In 1964 a ban on excavation was issued by the government to protect Moen jo Daro from excessive erosion caused by a high water table. And in 1973, experts from the member countries of UNESCO and officials of the government of Pakistan prepared and approved a master plan suggesting methods to combat waterlogging and salinity to save the site. The master plan was updated in 2006, but the ban on excavation continues and much of the archaeology remains submerged in underground water table. It is true that the site has outlived the forecast made by H.J. Plenderleith in 1964, “If nothing is done to preserve them, all the existing excavations will crumble within the next 20 to 30 years and one of the most striking monuments of the dawn of civilization will be lost for ever”, but it may not be able to survive violent methods of vandalism threatening regions of Pakistan.

Fortunately new technology and “digital preservation” have come to the rescue of many sites the world over; now Moen jo Daro needs to get ready for its virtual survival, at the very least. Digitization is no longer limited to textual and photographic material and the whole site can be preserved, stored, and retrieved digitally. In the face of the current law and order situations in Pakistan, where tourists and experts may fear to visit the site, accessing its digital content can be a comfortable option for them, while ensuring complete records should hostile forces purposely destroy the ancient remains of the city.

REFERENCES

(1) Walter A. Fairservis, Jr., “The origin, Character and Decline of an Early Civilization,” in Ancient Cities of the Indus, ed. Gregory Possehl, Vikas, New Delhi, 1979.

(2) Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark, Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, Oxford University Press, Pakistan, 1998.

(3) International Standard Bible Encyclodedia:Vol 1, Wm.B. Eerdmans, 1979 ed.

The Great Bath at which early archaeologists believed a water cult may have been performed. Photo courtesy of Amean J.

The ruins of Moen jo Daro with the Citadel Mound in the background. Photo courtesy of Amean J.

A seal of a unicorn.